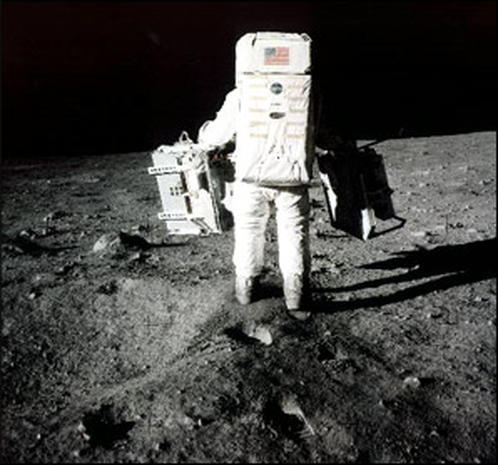

Indeed, it might even be said that the knowledge we have acquired about the moon has only created fodder for new and even, perhaps, greater flights of fancy. And yet, as “Apollo’s Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography,” the new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art – designed to coincide with the 50th anniversary of NASA’s historic moment – demonstrates, the moon, despite the revelation of many of her secrets, remains a source of wonder. By rights, the moon should have released much if not all of her strange hold over us. Then, on July 20, 1969, NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong stepped down from the Lunar Lander and placed the first human footprint on a body in our solar system other than Earth. Lunacy is a word with a history, an etymology rooted in myth, not a diagnosis.

THE MAN ON THE MOON PICTURES FULL

The full moon, as it turned out, didn’t turn us into werewolves or drive us mad. The tides that the moon makes became the measurable consequences of gravity. The Maria – seas in Latin – that we imagined there turned out to be vast plains of dark basalt. Wells’ Selenites, from his novel First Men in the Moon, no longer live beneath the lunar surface. NEW YORK CITY – When a mystery loses its mystery, when something we have seen as beyond human understanding is brought, through science, into what Nathaniel Hawthorne called the “realm of ordinary experience,” we reclassify it, place it among the things that used to amaze us, but no longer do, at least not in the same way. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Gelatin silver transparency on glass, overall 18-11/16 by 15¾ inches. “Transparency of the Moon from Negatives Made at the Lick Observatory, Mount Hamilton, California,” circa 1896.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)